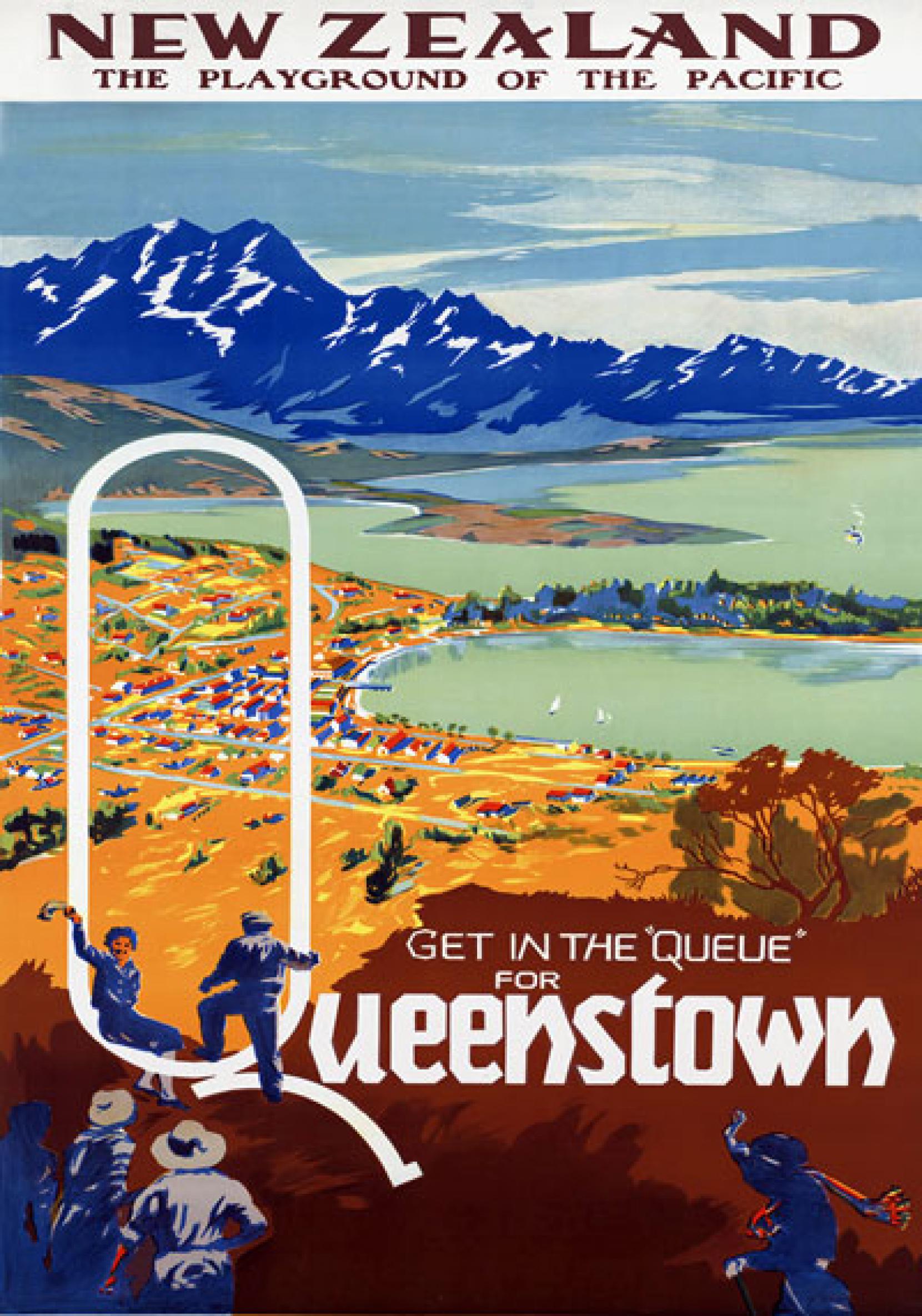

Maori History

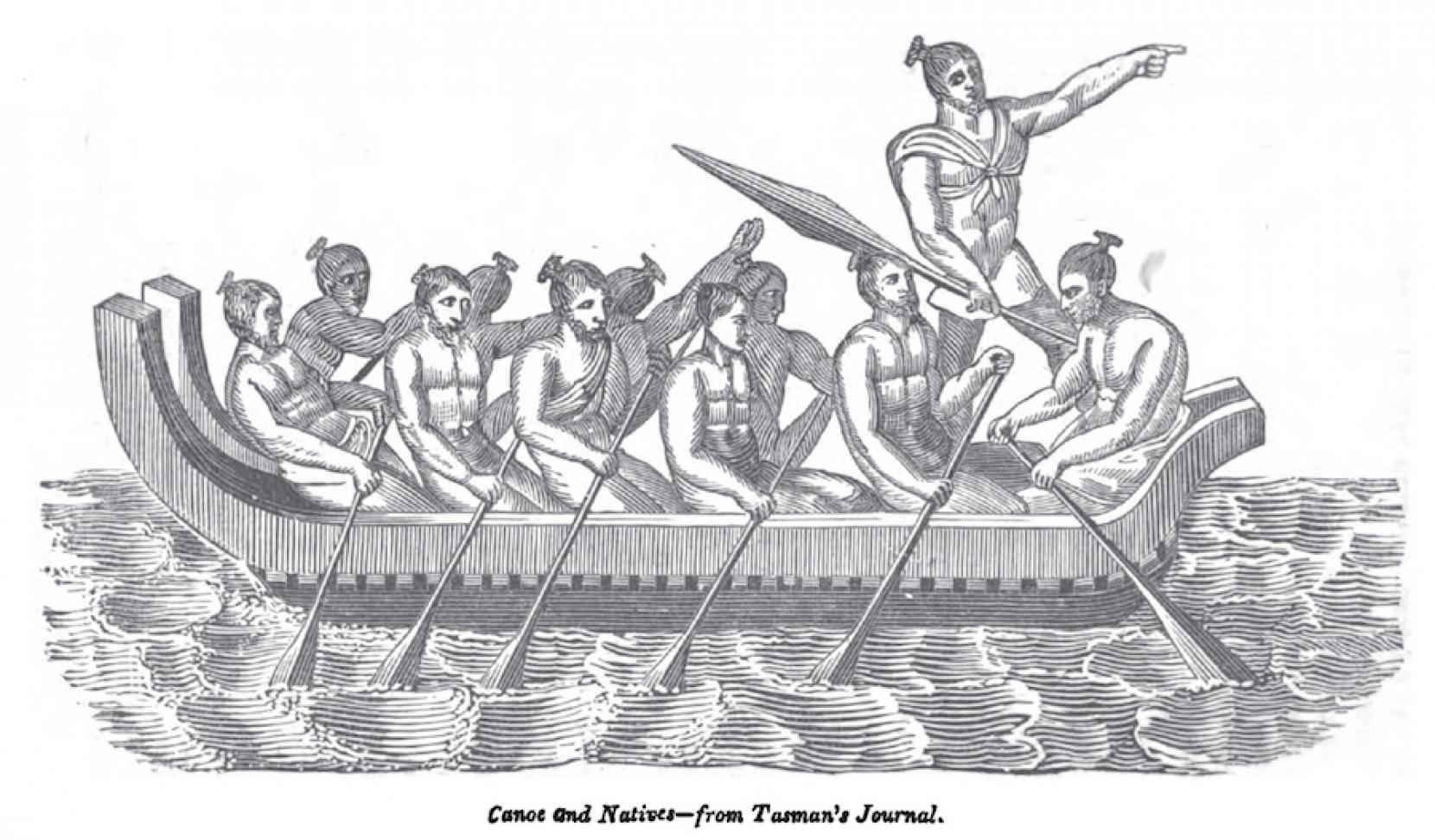

Polynesians first hunted in the Queenstown area in 1200AD, but found it a bit cold for permanent settlement. Maoris also travelled to Queenstown from the West Coast in search of food, stone and fibre. They used the area as a resting place and hunted the now extinct moa (you can see a statue of this giant bird in Earnslaw Park), though they also found the region a bit too cold to live in year-round.

At the head of the lake, near modern day Glenorchy, Maori travellers found pounamu (greenstone). The highly prized pounamu was used to create tools and beautiful ornaments. Carved pounamu pendants are still popular today and are often presented as a special gift, or as a symbolic keepsake for a traveller.

The Maori name for Queenstown is Tāhuna, meaning shallow bay.

Pastoral History

Scotsman Nathanael Chalmers was the first European to see Lake Wakatipu, in September 1856; he was led there by Reko, a Maori chief.

In 1860, William Gilbert Rees and Nicholas Paul Baltasar von Tunzlemann took the Crown Range route between Wanaka and Queenstown. Rising to 1,121 metres it’s now the highest main road in New Zealand and an easy route between the two towns in the summer months (note: it can be a difficult drive during winter!) But in Tunzlemann and Rees’ day, it was a difficult and dangerous route year-round.

The pair were the first to settle permanently in the area. Rees established his homestead in the heart of what’s now Queenstown’s CBD and Tunzlemann ran sheep and worked the land at the other side of the lake.

Their quiet existence was short lived…

Gold History

Jack Tewa, a Maori shepherd who was working for Rees, discovered alluvial gold in the Arrow River in 1862. It wasn’t long until his fellow workers, William Fox and John O’Callaghan found significant deposits and the gold rush began.

Miners flooded in from the Australian and Californian goldfields and a canvas shanty town sprung up on Rees’ farm. Rees was paid 10,000 pounds (the commonly used currency at that time) to give up his land and he turned his wood shed into a hotel called the Queen’s Arms. This later became Eichardt’s Hotel.

Tunzlemann was not so lucky. Many of his sheep died and eventually, he was forced to leave his land.

The Shotover River became the second richest gold bearing river in the world, but the rush didn’t last long. Within two years the gold began to run out and in 1864, miners followed the rush to West Coast where more gold had been found.

Income tax on the gold had been a big source of income for region, so the government invited Chinese miners to work on the Otago goldfields. More than 5,000 Chinese were living and working in the area by the 1870s. They worked hard to find gold left behind after the initial rush, but few made enough money to return home. They set up market gardens and worked as builders to supplement their meagre income and lifestyle.

Tourism History

Infrastructure put in place during the gold rush made it easier for tourists to get to Queenstown. Hotels were built at Kinloch and Glenorchy in the mid-1870s and the Dunedin to Kingston railway was established shortly afterward.

At first, tourists flocked to Queenstown in Summer for hiking and walking. It wasn’t until the 1940s that the Mount Cook Company kick-started Queenstown’s reputation as a Winter resort too. In 1947, the company hired a ski instructor and put in a tow rope on Coronet Peak.

1960 saw the first commercial jet boat rides and in 1988, the world’s first commercial bungee jumping began thanks to entrepreneurs AJ Hackett and Henry Van Asch.

Growth has skyrocketed since the 1950s, and now Queenstown offers a whole range of activities and experiences.